Many, if not all, of our courses in this program addressed acting leading in moral and ethical ways, prioritizing non-negotiable values, and putting diverse student needs at the center of our practice. Some courses that explicitly addressed this standard include:

- Leadership in Education

- Engaging Communities

- Moral Issues in Education

- Culturally Responsive Education

In Moral Issues in Education and Culturally Responsive Education, we directly addressed a variety of moral issues faced by educators including

- race, ethnicity and cultural identity

- religion and spirituality

- politics and charged discussions

- access

- parents and community

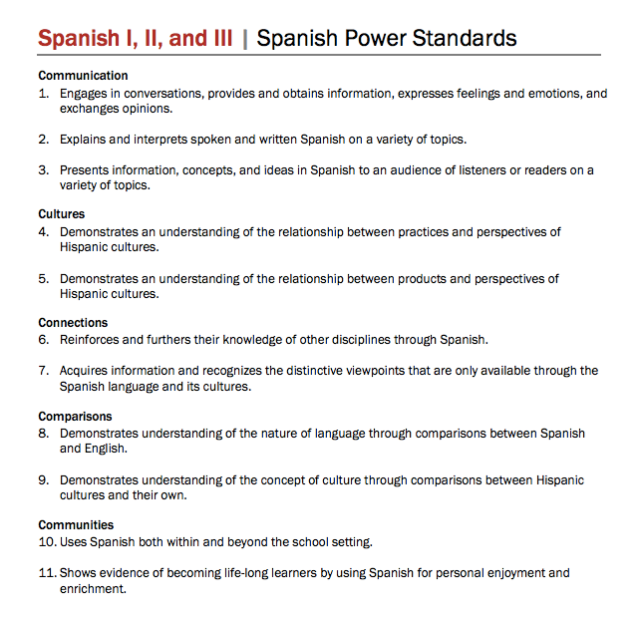

- school materials and curriculum

In The Charged Classroom: Predicaments and Possibilities for Democratic Teaching, Pace discusses the conflicts and forces that push and pull teachers in their pursuit of educating students prepared for entering a democratic society where they need to be able to think critically, question authority, respect and dialogue with diverse perspectives, practice empathy, dialogue with dissenting opinions, and work for social justice. Pace outlines three key areas of conflicts in classrooms: complex dynamics in classrooms, insufficient preparation and ongoing professional development to support and develop teachers ability to facilitate democratic discussion and dialogic conflict, and the contradictory curricular demands that are driven by social and political agendas.

Pace mentions that “we know a great deal in theory about how to [facilitate dialogue about controversial topics], but are still stumped by its minimal existence, especially in racially diverse and lower track settings.” (64) I however am not surprised by the minimal existence of meaningful dialogue around controversial topics, as I too have wanted to stimulate these conversations but had considerable reservations, especially after speaking to colleagues about this issue. I actually had a school counselor last year advise me to send a parent consent letter home first before talking about race and culture in my Spanish classroom! Many of us have heard of teachers right hear in the Greater Seattle Area who have lost their jobs after teaching curriculums centered around controversial topics. Teachers are intimidated by confrontation and heated controversy.

There is a notable lack of professional development in strategies that facilitate these dialogic situations in classrooms, especially those made of up students from diverse backgrounds. Furthermore, teachers need to know with certainty and confidence that administrators support and share a value for democratic discussion and dialogue in the classroom and the inherent conflict that comes with it. Teachers need to know that they will be supported not only through professional development, but also if a conflict with families arises. Teachers need to recognize that there are dialogic skills that need to be explicitly taught to students, norms established, processes practiced in order for a structured and respectful dialogue/discussion to be successful. This takes time and intentionality, and training teachers in these strategies would obviously help. Often times, if a teacher has not been trained in a strategy, tries it , and is unsuccessful due to a lack of structure, there is often a tendency to blame the strategy or say it’s not appropriate for the student group for one reason or another and the teacher is often unlikely to try again.

I believe that the ideals of teaching students to think critically, question for themselves, express unique opinions and ideas, and dialogue respectfully with others, especially in charged situations, are those which we MUST place at the center of our teaching. I agree with Pace’s call for more meaningful and readily available professional development for teachers and administrators. As Pace says, we cannot expect teachers to just figure out how to do something they don’t already know, we must lead them there.

I found Religion in the Classroom engaging on a topic that, as highlighted often in the text, is so rarely discussed in educational settings but so deeply shapes our lives and the way citizens of our society interacts. There are many parallels drawn here with our previous text, The Charged Classroom: Predicaments and Possibilities for Democratic Teaching, especially in the call to teachers to create spaces where dialogue regarding “controversial” topics, like religion and religious influences on our society, values systems, and politics can take place in the classroom, teaching students that “respect requires understanding but not endorsement, civic humility doesn’t require ethical relativism of core beliefs, and civic deliberation doesn’t require consensus, but rather continued conversation” and thereby helping cultivate mindful and empathetic democratic citizens. (p. 82)

On page 3, James mentions that she was “equally concerned about [Christina] feeling ostracized within the teacher education program and her accusations that those of us claiming to be “democratic educators” were acting in hypocritical ways.” This is a critical reflection, as so many times when a student voices an intolerant opinion or one that does not recognize the reality of a society with pluralistic views and beliefs, we often do not challenge these students due to a lack of confidence in how to do so, an avoidance of conflict, or an avarice to bring religious conversation into the public realm, due the conflict we might encounter amongst students or push back from families. Often, we can help build understanding and demonstrate respect for others with differing belief systems, simply by opening up the conversation. Ask, start the conversation, don’t just ignore religious conversations. On page 57, Simone Schweber discusses the awkwardness that a Jewish student studying the Holocaust as one of the only Jewish students in the class feels, but by simply asking her what it feels like to be in this situation, one can not only learn how to better meet this student’s needs in the classroom, but can also open the door to exploring the role religion plays in our personal identities, value systems and ways we perceive the world and actions around us.

The discussion around unconscious values was particularly intriguing for me. I was surprised by the example of how religious views can shape one’s perceptions of poverty and wealth, for example. I had never thought of this before, and what a unique challenge it presents in the classroom as these values are often not shared vocally. This emphasizes the need for pre-assessments and frequent formative assessment to gain a better understanding of students’ perceptions, values and misconceptions of the content. This is a very important reason why students don’t always learn what we teach!

Over and over again it is suggested here that as teachers it is our duty to create safe spaces to discuss religion in our classrooms. On page 59 Schweber suggests that “we do our utmost as teachers to raise these ideas and discuss them. I want us, as teachers, whether in public or private schools, to consider it part of our work to put religious ideas on the table. I want them to be part of classroom conversations…” It seems that in order for this to really happen, as was suggested in The Charged Classroom: Predicaments and Possibilities for Democratic Teaching as well, teachers need better professional development and more whole school support in order to outfit them (us) with the strategies to create safe spaces where opinions/ideas can be shared and explored collectively through dialogue in the

Norman Wirzba’s book Way of love: Recovering the heart of Christianity discusses the fundamental characteristic of love in shaping the Christian religious tradition. I found this book inspiring personally, but less relevant for my teaching life in public schools. Obviously there is much love, dedication and consideration of others in our profession, but the need to love our students unconditionally was not a revelation. I appreciated the thoughtful way in which Wirzba connected Christian traditions with modern life examples, as I have often found this lacking.

Another resource with many thought-provoking essays regarding social justice and morality issues we are faced with every day is the This I Believe Essay Collection. There were many essays I listened to that made me think or appreciate the author’s sincerity, but the one I liked the most was “I can make a difference” by Carol Fixman (http://thisibelieve.org/essay/170999/). In her essay, she speaks to the lesson she learned from her mother that she can be a person of action, to be the change-maker in her own life, to create the kind of relationships she wants to see in the world and to push back on injustices she pays witness to around her.

I found this particular essay inspirational, as it can be easy for me to get caught in the “oh I will do it tomorrow,” mode. There is always something else more pressing, more urgent to attend to, and I often don’t get around to all those things I was intending to do. I find upon reflection that often the activities I neglect are those most beneficial to myself and my community, such as saving time for meditation and personal reflection, exercise, engaging in public dialogue about community issues and injustice, but as they are more challenging or time consuming and require more intentionality, they often get pushed to the back burner and remain on the “to-do” list forever. This essay has inspired me by reminding me that I do strongly believe that change is always possible: in our students, our classrooms, our society, our relationships, and in ourselves. But I must be my own change maker.

A public dialogue about belief – one essay at a time. (n.d.). Retrieved June 04, 2017, from http://thisibelieve.org/

Blankstein, A.M, Cole, R.W., & Houston, P.D. (2007). Spirituality in educational leadership.Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

James, J.H., Schweber, S., Kunzman, R., Barton, K.C., & Logan, K. (2015). Religion in the classroom: Dilemmas for democratic education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Pace, J. (2015). The charged classroom: Predicaments and possibilities for democratic teaching. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wirzba, N. (2016). Way of Love: Recovering the Heart of Christianity. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

Wiliam suggests four stages to embedding formative assessemnt ito our work with fidelity:

Wiliam suggests four stages to embedding formative assessemnt ito our work with fidelity:

Before taking the EDAD 6580 – Leadership in Education course with Dr. Alsbury, I knew very little about leadership theory and leadership styles, other than that which I had experienced and could discuss anecdotally. This course work and connected reflection helped highlight the importance of recognizing that who we are as individuals greatly influences our leadership style and preferences.

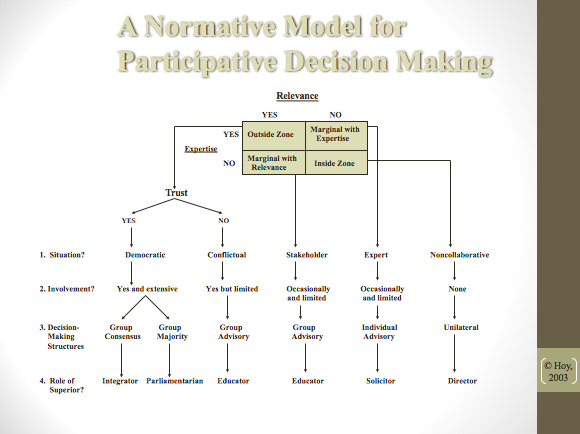

Before taking the EDAD 6580 – Leadership in Education course with Dr. Alsbury, I knew very little about leadership theory and leadership styles, other than that which I had experienced and could discuss anecdotally. This course work and connected reflection helped highlight the importance of recognizing that who we are as individuals greatly influences our leadership style and preferences. Management style according to the X-Y Theory Questionnaire. According to the Managerial Grid, I am strongest in the “Sound” managerial style that is characterized by examining what is right versus who is right. However, I also have tendencies toward the “Accommodating” and “Indifferent” styles. According to the Leadership Survey, I demonstrated a tendency towards a high task and high relationship style of leadership, but also with a second tendency to a high relationship and low task style of leadership. This parallels the results from the Managerial Grid and calls attention to weaknesses that can come about from too much emphasis on relationships and not enough follow through regarding high standards and consistently high expectations for everyone in the organization.

Management style according to the X-Y Theory Questionnaire. According to the Managerial Grid, I am strongest in the “Sound” managerial style that is characterized by examining what is right versus who is right. However, I also have tendencies toward the “Accommodating” and “Indifferent” styles. According to the Leadership Survey, I demonstrated a tendency towards a high task and high relationship style of leadership, but also with a second tendency to a high relationship and low task style of leadership. This parallels the results from the Managerial Grid and calls attention to weaknesses that can come about from too much emphasis on relationships and not enough follow through regarding high standards and consistently high expectations for everyone in the organization.